Acute Myeloid Leukaemia

Learn about acute myeloid leukaemia

Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) occurs due to an overproduction of the myeloid white blood cells – sometimes called ‘myeloblasts’. These abnormal cells overcrowd the bone marrow and can also spill out to build up in parts of the lymphatic system (the spleen or lymph nodes) and in the liver.

Acute Myeloid Leukaemia is not one disease – it has been suggested to encompass up to 8 sub-groups. While generally, symptoms are common across AMLs, sometimes the type of AML can have more specific side-effects.

For example, in some types of AML, leukaemia cells tend to spread from the blood to other parts of the body (such as the gums), causing discomfort and swelling. Whereas Acute Promyelocytic Leukaemia (APML or M3) – another type of AML – is more associated with abnormalities in blood clotting and bleeding.

More general symptoms of AML are caused by a lack of normal blood cells. These include:

- Anaemia

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Frequent Infection (because the cancer undermines the normal role of healthy white blood cells to fight disease and infection.)

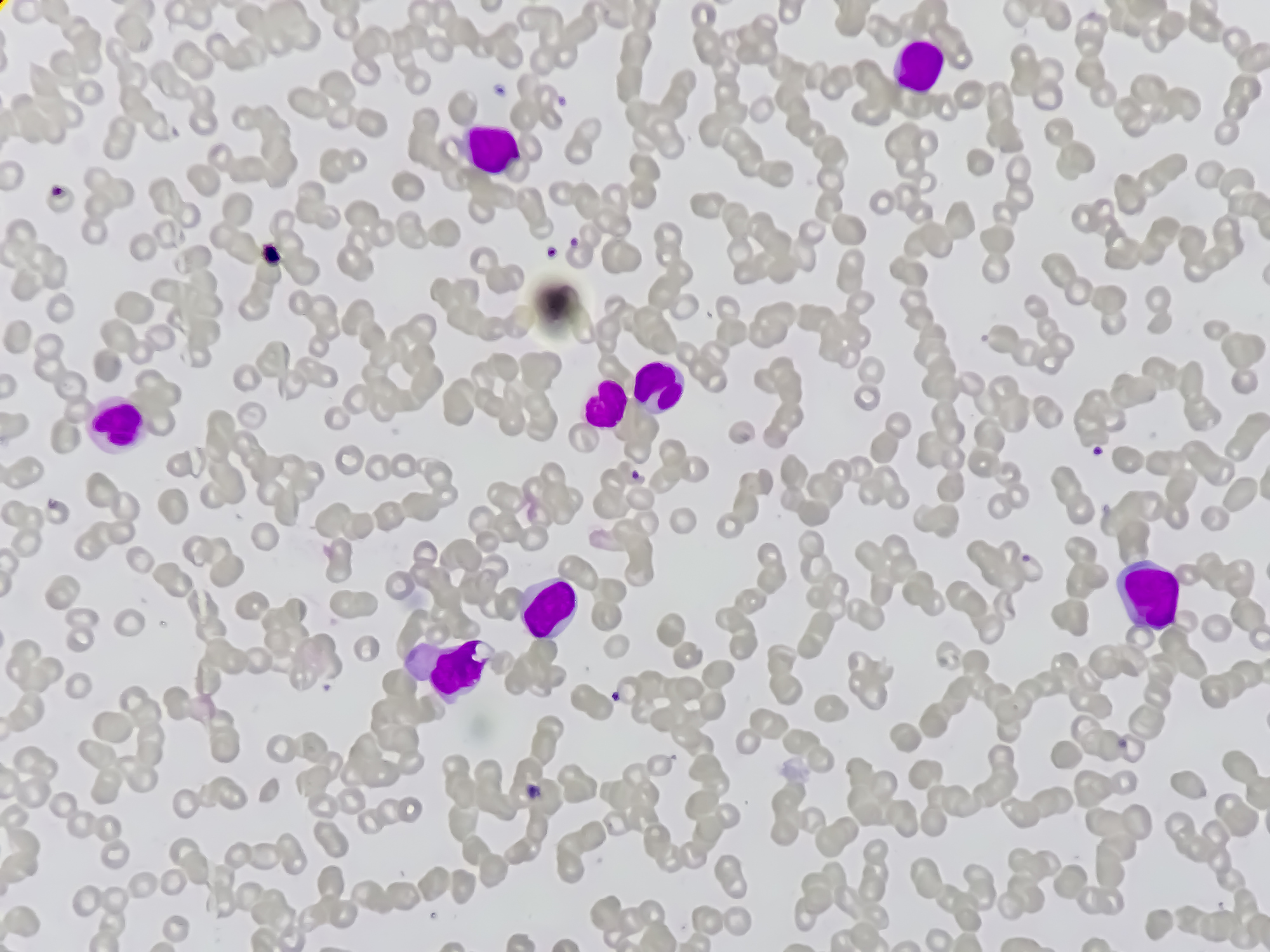

AML is diagnosed by a full blood count, a bone marrow biopsy and an examination.

The most decisive way to predict an AML prognosis is to assess the genetic fingerprint of the leukaemia cells.

Certain changes within the cell DNA will indicate a more favourable prognosis compared with others, with the most positive diagnosis being Acute Promyelocytic Leukaemia (APML or M3). This subtype of AML usually has the best overall prognosis.

The main form of treatment for AML will be chemotherapy, with drug combinations personalised as much as possible to each individual. The aim of treatment will be to achieve remission, where there is no evidence of remaining leukaemia cells in the blood and to restore normal blood cell levels.

During this time, patients are likely to need antibiotics and other drugs to treat, or prevent infection. Blood or platelet transfusions may also be required to restore normal blood count. Once in remission, a maintenance period of treatment is required to ensure minimal risk of relapse.